By Sirat Gohar Daudpoto for Invisiblites

Hearing about archeology or an archeologist, people usually show a desire to know about this profession. In a country like Pakistan where the gap between archeology and the public is very big, archeology is unknown to most of the individuals interacting with the archeologists. That is why people seem more interested in knowing about it. If you are an archeologist from Pakistan, you would be asked the following questions repeatedly. What do you do? What is archeology? And why is it important? On the other hand, archeology’s interrelation with people’s past and identity makes it interesting to those among the public who are educated and are already aware of archeology and the work of archeologists.

What is Archeology

To describe in a few words, the study of the ancient past through material remains is called archeology, whereas, an archeologist is the one who writes the stories of the human past based on the cultural materials (e.g. objects, mounds, structures, and so on) that is recorded in the course of fieldwork: excavation or survey. In addition to excavation and survey, archeologists’ tasks include documentation, preservation, and promotion of archeological heritage and dissemination of archeological information. But the most important of these is how an archeologist presents objects from the past into the present. Transmitting information about archeology to the general public is as important as digging in archeology.

Archeology and Identity

Archeology and identity are interrelated, and archeologists need to understand the interrelationship between the two. For example, before the discovery of the Indus Civilization, it was believed that the civilizational history of the subcontinent was not older than the Vedic Aryans, but when Sir John Marshall announced the discovery of the Indus Civilization, through an article published in the Illustrated London News in 1924 in which he wrote that the history of India (and Pakistan) is five thousand years old, the historical background of the subcontinent changed. This news had a great impact on the nationalists who later objected to the history of the subcontinent written by the British. In this regard, archeological publications in the native languages are of great importance. Particularly, R.D. Banerji’s writings on Mohenjodaro in the Bengali language and a number of articles and books on the archeology of Sindh, especially Mohenjodaro and the Indus Civilization, written by the Sindhi authors, whose writings influenced the educated class of Sindh and created awareness among the people that the civilization of subcontinent is thousands of years old, forming the identity of the local people.

How a Bengali Woman Pioneered the Concept of Female Utopia – Invisiblites

Archeologists’ Neglect

Archeology has a long history in Pakistan. It has been practiced in this part of the world before the establishment of the Archeological Survey of India in 1961 which, for the first time at the governmental level, provided a platform for doing archeology in the Indo-Pak subcontinent. Despite its long-time presence in the region, the majority of the people have no familiarity with archeology or things archeological. Call it the failure of Pakistani archeologists or the reason for not paying attention to the popularity of archeology that too is the work of archeologists. By keeping their activities away from the public and by not engaging with the general audience at an appropriate time and place, archeologists have, intentionally or unintentionally, widened the gap between archeology and the people. For example, the foreword of the book titled “Wad-i-Sindh Ki Tehzeeb” written in Urdu by Muhammad Idress Siddiqui is the best example of archeologists’ negligence regarding communication with the public. In the foreword, Siddiqui writes about his encounters with the people during the fieldwork in Panjgur and Bahawalpur who were curious to know about archeological work. The foreword starts with a question asked to the author by a local laborer “[trans.] Sir! Why are you digging this mound?”, and he also writes about an educated (?) young man who asked him: “[trans.] What we will do with these potsherds?”. The author did not respond to their questions, they were intentionally avoided as the author himself mentioned.

In the course of work and ordinary life, archeologists come across different types of people, some of whom would be literate but the majority less educated and illiterate. Usually during the fieldwork, archeologists interact with the public. People ask them questions about their activities and the importance of doing archeology. This is the ideal situation and an opportune moment archeologists should take advantage of because direct conversation with people is the easiest way of transmitting and popularizing (archeological) information. However, if we look at the history of Pakistani archeology and its popularity, it will be felt that the target of the archeologists throughout has been only the elite and/or the educated class and that archeology, to a greater extent, has been kept away from the common people. There may be several reasons for this, such as personal preferences, financial gains, and political motives of the archeologists. But using archeology for personal gains and purposes is ‘false archeology’, as defined by a famous English archeologist Glyn Daniel who on the other hand defines ‘true archeology’ as the scientific progress in the field. Generally, Pakistani archeologists seem more influenced by the outside and much less by the progress in archeology. Due to this, great damage has been done to the country’s national heritage and the educational institutions where archeology is being taught and practiced.

Concluding Remark

Archeology is important because it helps us make a sense of the past: how people lived, what they ate or wore, what the environment was like, and a lot more. It is the best way of understanding the evolution of human life. And that is why it is interesting to common people. Archeologically speaking, it is the duty of archeologists to disseminate archeological knowledge and inform the public about archeological discoveries and heritage; that certainly is ‘true archeology’. Without people, archeology has no use, and archeologists should be aware of the fact that archeology cannot progress without public involvement.

[Sirat Gohar Daudpoto is an archeologist and cultural heritage specialist. He is the Project Manager of the Taxila Museum at The Citizens Archive of Pakistan and a PhD candidate at the Taxila Institute of Asian Civilization, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad.]

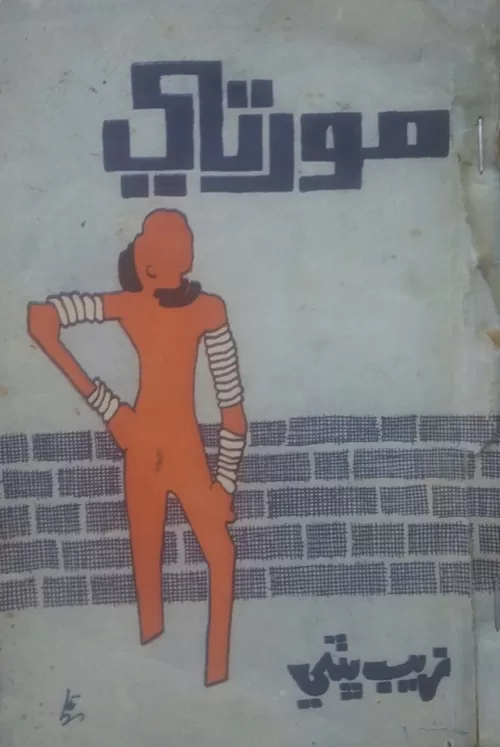

Photo credits: The title page of a Sindhi novel showing a 4500-year-old figurine of a lady; taken by the author in 2018.